I have written several articles the environment. A list of links have been provided at bottom of this article for your convenience. This article will, however address different aspects on the environment and the planet in general.

Table of Contents

-The Evolution of Sharks

-Shark Evolution Timeline

-How did sharks survive five mass extinction events?

–Biological classification

-Types of Sharks

-Extant Shark Orders

-Shark Anatomy

-Shark Attacks

-Reasons for Attacks

-Shark Conservation

-Notable Researchers and People

-Top Five Extinctions

-Shark Finning

–What The extinction of Sharks means for the World

-5 Things you didn’t know sharks do for you.

–Sharks in The Media

–Safe Practices for Swimming with Sharks

-New Shark Facts

-Environmental Postings

-Scared of sharks? This photographer aims to turn shark fear into fascination

The Evolution of Sharks

Sharks first appear in the fossil record roughly 420 million years ago, a time when fishes began to evolve. The ocean was a very different landscape, with most creatures lacking a backbone. Trilobites, creatures distantly related to spiders and horseshoe crabs, scurried across the seafloor while shelled cephalopods, relatives of squid and octopus, reigned as the top predators above in the water column. Chimaeras are cartilaginous fishes, but not technically sharks. It is thought that sharks and chimaeras may have diverged up to 420 million years ago. The earliest shark-like teeth we have come from an Early Devonian (410-million-year-old) fossil belonging to an ancient fish called Doliodus problematicus. Described as the ‘least shark-like shark’, it is thought to have risen from within a group of fish known as acanthodians or spiny sharks. By the middle of the Devonian (380 million years ago), the genus Antarctilamna had appeared, looking more like eels than sharks. It is about this time that Cladoselache also evolved. This is the first group that we would recognize as sharks today, but it may well have been part of the chimaera branch, and so technically not a shark. As active predators they had torpedo-shaped bodies, forked tails and dorsal fins.

An extinction event at the end of the Devonian killed off at least 75% of all species on Earth, including many lineages of fish that once swam the oceans. This allowed sharks to dominate, giving rise to a whole variety of shapes and forms. By the Early JurassicPeriod (195 million years ago) the oldest-known group of modern sharks, the Hexanchiformes or sixgill sharks, had evolved. They were followed during the rest of the Jurassic by most modern shark groups. By the Carboniferous and Permian periods, sharks of all kinds roamed the world’s seas. The lineage leading to the megalodon first appeared about 60 million years ago. The megalodon is a member of the lineage of lamnoid sharks (Lamniformes), which also include the great white, mako and thresher sharks, among others. This lineage can be traced back to the Cretaceous Period.

At the beginning Cretaceous of Period (145 million to 66 million years ago) sharks were once again widely common and varied in the ancient seas, before experiencing their fifth mass extinction event. Fossil teeth show that the asteroid strike at the end of the Cretaceous killed off many of the largest species of shark. Only the smallest and deep-water species that fed primarily on fish survived. While much of life became extinct during the End-Cretaceous extinction event, including all non-avian dinosaurs, sharks once again persisted. Sharks soon began to increase in size once again, and continued to evolve larger forms throughout the Palaeogene (66 to 23 million years ago). It was during this time that Otodus obliquus, the ancestor to megalodon (Otodus megalodon), appeared. Despite what many might think, megalodon is not related to great white sharks. In fact it may have been in competition with the great white shark’s ancestors, which evolved during the Middle Eocene (45 million years ago) from broad-toothed mako sharks.

Around 2.6 million years ago, around the time when the megalodon disappears from the fossil record, large mammals in the ocean were undergoing significant changes in response to a changing climate. At the beginning of the Miocene, marine mammals were at the height of their diversity and abundance. But later during the Pliocene, there was a drop in ocean temperatures that likely contributed to the megalodon’s demise. For much of the Cenozoic Era, a seaway existed between the Pacific and Caribbean that allowed for water and species to move between the two ocean basins. Pacific waters, filled with nutrients, easily flowed into the Atlantic and helped sustain high levels of diversity. That all changed when the Pacific tectonic plate butted up against the Caribbean and South American plates during the Pliocene, and the Isthmus of Panama began to take shape. This tectonic collision caused volcanic activity and the formation of mountains that stretched from North to South America. As the Caribbean was cut off from the Pacific, the Atlantic Ocean became saltier, and the Gulf Stream strengthened and propelled warm water from the Equator up into the north. Today, the salty water of the Atlantic is a major engine for global ocean circulation. Ecosystems, too, reacted to the closure of the seaway. Cordoned off from the nutrient-rich waters of the Pacific, Caribbean species needed to adapt. The barrier led to the creation of pairs of related species, such as the Pacific goliath grouper and the Atlantic goliath grouper, but other species didn’t fare so well. It is likely that the giant megalodon was unable to sustain its massive body size due to these changes and the loss of prey, and eventually went extinct. ( Smithsonian Institution Article “The Megaladon” by Danielle Hall)

How did sharks survive five mass extinction events?

There is no single reason sharks survived all five major extinction events – all had different causes and different groups of sharks pulled through each one. One general theme, however, seems to be the survival of deep-water species and the dietary generalist. It is possible that shark diversity may also have played an important role. Sharks are able to exploit different parts of the water column – from deep, dark oceans to shallow seas, and even river systems. They eat a wide variety of food, such as plankton, fish, crabs, seals and whales. This diversity means that sharks as a group are more likely to survive if things in the oceans change.’

Biological classification:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Chondrichthyes

- Subclass: Elasmobranchii

- Superorder: Selachimorpha

Types of sharks

List of sharks Subdivisions of the biological classification Selachimorpha include:

- Carcharhiniformes – ground sharks

- Heterodontiformes – bullhead sharks

- Hexanchiformes – the five extant species of the most primitive types of sharks

- Lamniformes – mackerel sharks

- Orectolobiformes – includes carpet sharks, including zebra sharks, nurse sharks, wobbegongs, and the whale shark

- Pristiophoriformes – includes sawsharks

- Squaliformes – includes gulper sharks, bramble sharks, lantern sharks, rough sharks, sleeper sharks and dogfish sharks

- Squatiniformes – angel sharks

- † Cladoselachiformes

- † Hybodontiformes

- † Symmoriida

- † Xenacanthida (Xenacantiformes)

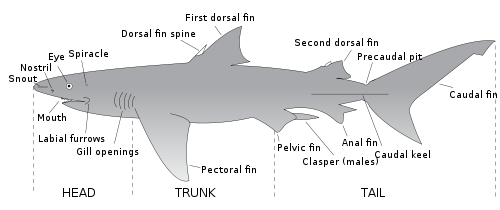

Shark anatomy

- Physical characteristics of sharks – shark skeleton, respiration and skin

- Dermal denticle – small outgrowths which cover the skin of sharks

- Ampullae of Lorenzini – sensing organ that helps sharks and fish to sense electric fields

- Electroreception – the biological ability to perceive electrical impulses (see also Ampullae of Lorenzini)

- Lateral line – sense organ that detects movement and vibration in the surrounding water

- Shark cartilage – material that a sharks’ skeleton is composed of

- Shark teeth

- Spiracle – pumps water across gills

- Clasper – the anatomical structure that male sharks use for mating

- Fish anatomy – generic description of fish anatomy

Shark Attacks

A shark attack is an attack on a human by a shark. Every year, around 80 unprovoked attacks are reported worldwide. Out of more than 489 shark species, only three are responsible for a double-digit number of fatal, unprovoked attacks on humans: the great white, tiger, and bull. The oceanic whitetip has probably killed many more castaways, but these are not recorded in the statistics.

Only a few species of shark are dangerous to humans. Out of more than 480 shark species, only three are responsible for two-digit numbers of fatal unprovoked attacks on humans: the great white, tiger and bull; however, the oceanic whitetip has probably killed many more castaways which have not been recorded in the statistics.

These sharks, being large, powerful predators, may sometimes attack and kill people, notwithstanding the fact that all having been filmed in open water by unprotected divers.

In addition to the four species responsible for a significant number of fatal attacks on humans, a number of other species have attacked humans without being provoked, and have on extremely rare occasions been responsible for a human death. This group includes the shortfin mako, hammerhead, Galapagos, gray reef, blacktip, lemon, silky shark and blue sharks. These sharks are also large, powerful predators which can be provoked simply by being in the water at the wrong time and place, but they are normally considered less dangerous to humans than the previous group.

Provoked attack

Provoked attacks occur when a human touches, hooks, nets, or otherwise aggravates the animal. Incidents that occur outside of a shark’s natural habitat, such as aquariums and research holding-pens, are considered provoked, as are all incidents involving captured sharks. Sometimes humans inadvertently provoke an attack, such as when a surfer accidentally hits a shark with a surf board.

Unprovoked attack

Unprovoked attacks are initiated by the shark—they occur in a shark’s natural habitat on a live human and without human provocation. There are three subcategories of unprovoked attack:

- Hit-and-run attack – usually non-fatal, the shark bites and then leaves; most victims do not see the shark. This is the most common type of attack and typically occurs in the surf zone or in murky water. Most hit-and-run attacks are believed to be the result of mistaken identity.

- Sneak attack – the victim will not usually see the shark, and may sustain multiple deep bites. This kind of attack is predatory in nature and is often carried out with the intention of consuming the victim. It is extraordinarily rare for this to occur.

- Bump-and-bite attack – the shark circles and bumps the victim before biting. Great whites are known to do this on occasion, referred to as a “test bite”, in which the great white is attempting to identify what is being bitten. Repeated bites, depending on the reaction of the victim (thrashing or panicking may lead the shark to believe the victim is prey), are not uncommon and can be severe or fatal. Bump-and-bite attacks are not believed to be the result of mistaken identity.

Reasons for attacks

Large sharks species are apex predators in their environment, and thus have little fear of any creature (other than orcas) with which they cross paths. Like most sophisticated hunters, they are curious when they encounter something unusual in their territories. Lacking any limbs with sensitive digits such as hands or feet, the only way they can explore an object or organism is to bite it; these bites are known as test bites. Generally, shark bites are exploratory, and the animal will swim away after one bite. For example, exploratory bites on surfers are thought to be caused by the shark mistaking the surfer and surfboard for the shape of prey. Nonetheless, a single bite can grievously injure a human if the animal involved is a powerful predator such as a great white or tiger shark.

Feeding is not the reason sharks attack humans. In fact, humans do not provide enough high-fat meat for sharks, which need a lot of energy to power their large, muscular bodies.

A shark will normally make one swift attack and then retreat to wait for the victim to die or weaken from shock and blood loss, before returning to feed. This protects the shark from injury from a wounded and aggressive target; however, it also allows humans time to get out of the water and survive. Shark attacks may also occur due to territorial reasons or as dominance over another shark species, resulting in an attack.

Sharks are equipped with sensory organs called the Ampullae of Lorenzini that detect the electricity generated by muscle movement. The shark’s electrical receptors, which pick up movement, detect signals like those emitted from fish wounded, for example, by someone who is spearfishing, leading the shark to attack the person by mistake. George H. Burgess, director of the International Shark Attack File, said the following regarding why people are attacked: “Attacks are basically an odds game based on how many hours you are in the water”.

Shark conservation

One of the first species of shark to be protected was the Grey nurse shark

- 1992 Cageless shark-diving expedition – first publicized cageless dive with great white sharks which contributed to changing public opinions about the supposed “killing machine”

- Shark Alliance – coalition of nongovernmental organizations dedicated to restoring and conserving shark populations by improving European fishing policy

- Shark Conservation Act – proposed US law to protect sharks

- Shark sanctuary – Palau’s first-ever attempt to prohibit taking sharks within its territorial waters

- Shark tourism – form of ecotourism showcasing sharks

- Shark Trust – A UK organisation for conservation of sharks

Notable researchers and people

- Peter Benchley – author of the novel Jaws, later worked for shark conservation

- Eugenie Clark – American ichthyologist researching poisonous fish and the behavior of sharks; popularly known as The Shark Lady

- Leonard Compagno – international authority on shark taxonomy, best known for 1984 catalog of shark species (FAO)

- Jacques-Yves Cousteau – French naval officer, explorer, ecologist, filmmaker, innovator, scientist, photographer, author and researcher who studied the sea and all forms of life in water including sharks

- Ben Cropp – Australian former shark hunter, who stopped in 1962 to produce some 150 wildlife documentaries

- Richard Ellis – American marine biologist, author, and illustrator.

- Rodney Fox – Australian film maker, conservationist, survivor of great white shark attack and one of the world’s foremost authorities on them

- Andre Hartman – South African diving guide best known for free-diving unprotected with great white sharks

- Hans Hass – diving pioneer, known for shark documentaries

- Mike Rutzen – great white shark expert and outspoken champion of shark conservation; known for free diving unprotected with great white sharks

- Ron & Valerie Taylor – ex-spearfishing champions who switched from killing to filming underwater documentaries

- Rob Stewart (filmmaker) – Canadian photographer, filmmaker and conservationist. He was best known for making and directing the documentary film Sharkwater (Source: Wikipedia)

This not my typical blog posting, mainly because of the nature of the subject. This is the broadest subject I have tried to cover. This covers 240 million years. Sharks have been around for a long time. They have survived 5 major extinction episodes.

Top Five Extinctions

- Ordovician-silurian Extinction: 440 million years ago.

- Devonian Extinction: 365 million years ago.

- Permian-triassic Extinction: 250 million years ago.

- Triassic-jurassic Extinction: 210 million years ago.

- Cretaceous-tertiary Extinction: 65 Million Years Ago.

Shark Finning

But sharks may not survive human habitation, the sixth great extinction. Since 1950, our species has eliminated 90% of the ocean’s large fish, including sharks. We kill over 10,000 sharks per hour, primarily due to our global appetite for seafood as non-targeted “by-catch” in commercial operations, for the shark fishing operations, for the shark fin trade, and in recreational fishing. We are decimating these important and ancient animals in a blink of a geological eye. But, unlike pandas and rhinos who are also endangered, very few organizations are rallying behind sharks. Perhaps it’s because we see them as primitive and vicious. But we don’t even understand the cascading effect losing these large ocean predators is having, and will continue to have, on our delicate and interconnected marine ecosystems. Losing millions of years of evolution due to one species’ irresponsible and cruel activities is beyond tragic.

What The extinction of Sharks means for the World

If the shark disappears from our oceans will be with exception of the trilobyte (which they found some living species), one of the oldest living remaining species on earth, will be gone forever. This extinction goes beyond a mere loss to our heritage. Sharks are an integral part of our ecosystem, their disappearance will have incalculable affects on the earth, with possible more extensive mass extinctions.

Before I continue discussing sharks, I want to take a brief detour, you will understand the reason for it when you read it. This is a quote from Jacques-Yves Cousteau. This is from the introduction of his landmark multi-volume work, “The Oceans of Jacques Cousteau“

“If the Oceans Should Die–that is, if life in the oceans were suddenly, somehow to become to an end–it would be the final as well as the greatest catastrophe in the troublous story of man and the other animals and plants with whom man shares the planet.

“To begin with, bereft of life the ocean would at once foul. Such a colossal stench born of decaying organic matter would rise from the ocean wasteland that it would of itself suffice to drive man back from all coastal regions. Far harsher consequences would soon follow. The ocean is earth’s principal buffer, keeping balances intact between the different salts and gases of which our lives are composed and on which they depend. With no life in the seas the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere would set forth on an inexorable climb. When this CO2 level passed a certain point the “greenhouse effect” would come into operation: heat radiating from earth to space would be trapped beneath the stratosphere, shooting up sea-level temperatures. At both North and South Poles the ice caps would melt. The oceans would rise perhaps 100 feet in a small number of years. All earth’s major cities would be inundated. To avoid drowning one-third of the world’s population would be compelled to flee to hills and mountains, hills and mountains unready to receive these people, unable to produce enough food for them. Among many other consequences of the death of the oceans, the surface would become coated with a thick film of dead organic matter, affecting the evaporation process., reducing rain, and starting global drought and famine.

“Even then the disaster would only be entering its terminal phase. Packed together on various highlands, starving, subject to bizarre storms and diseases, with families and societies totally disrupted, what is left of mankind begins to suffer from anoxia–lack of oxygen–caused by the extinction of plankton algae and the reduction of land vegetation. Pinned in the narrow belt between dead seas and sterile mountain slopes, man coughs out his last moments in unutterable agony. Maybe 30 to 50 years after the ocean has died the last man on earth takes his own last breath. Organic life on the planet is reduced to bacteria and a few scavenger insects.” Pretty powerful stuff.

Now back to sharks. As apex predators, sharks play an important role in the ecosystem by maintaining the species below them in the food chain and serving as an indicator for ocean health. They help remove the weak and the sick as well as keeping the balance with competitors helping to ensure species diversity. As predators, they shift their prey’s spatial habitat, which alters the feeding strategy and diets of other species. Through the spatial controls and abundance, sharks indirectly maintain the sea grass and corals reef habitats. The loss of sharks has led to the decline in coral reefs, sea grass beds and the loss of commercial fisheries. By taking sharks out of the coral reef ecosystem, the larger predatory fish, such as groupers, increase in abundance and feed on the herbivores. With less herbivores, macroalgae expands and coral can no longer compete, shifting the ecosystem to one of algae dominance, affecting the survival of the reef system. Oceana released a report in July 2008, “Predators as Prey: Why Healthy Oceans Need Sharks”, illustrating our need to protect sharks.

Sharks’ control over species below them in the food chain indirectly affects the economy. A study in North Carolina showed that the loss of the great sharks increased the ray populations below them. As a result, the hungry rays ate all the bay scallops, forcing the fishery to close. Without scallops to eat, the rays have moved on to other bivalves. The decline of the quahog, a key ingredient in clam chowder, is forcing many restaurants to remove this American classic from their menus. The disappearance of scallops and clams demonstrates that the elimination of sharks can cause harm to the economy in addition to ecosystems. Sharks are also influencing the economy through ecotourism. In the Bahamas, a single live reef shark is worth $250,000 as a result of dive tourism versus a one time value of $50 when caught by a fisherman. One whale shark in Belize can bring in $2 million over its lifetime.( The importance of sharks from eu.oceana.org)

5 Things you didn’t know sharks do for you.

1. Sharks keep the food web in check.

Many shark species are “apex predators,” meaning they reside at the top of the food web. These sharks keep populations of their prey in check, weeding out the weak and sick animals to keep the overall population healthy. Their disappearance can set off a chain reaction throughout the ocean — and even impact people on shore.

2. Sharks could hold cures for diseases.

It has puzzled researchers for years: Why don’t sharks get sick as often as other species? Shark tissue appears to have anticoagulant and antibacterial properties. Scientists are studying it in hopes of finding treatments for a number of medical conditions, including viruses and cystic fibrosis .

Copying sharks could even lead to significant global health impacts. Each year, more than 2 million hospital patients in the U.S. suffer from healthcare-acquired infections due to unsanitary conditions. Looking to shark skin’s unique antimicrobial properties, researchers were able to create an antibacterial surface-coating called Sharklet AF. This surface technology can ward off a range of infectious bacteria and help stop the proliferation of superbugs in hospitals.

3. Sharks help keep the carbon cycle in motion.

Carbon is a critical element in the cycle of life — and a contributor to climate change. By feeding on dead matter that collects on the seafloor, scavengers such as deep-sea sharks, hagfish and starfish help to move carbon through the ocean.

In addition, research has found that large marine animals such as whales and sharks sequester comparatively large amounts of carbon in their bodies. When they die naturally, they sink to the seafloor, where they are eaten by scavengers. However, when they are hunted by humans, they are removed from the ocean, disrupting the ocean’s carbon cycle.

4. Sharks inspire smart design.

People have been practicing biomimicry — imitating nature’s designs to solve human problems — for many years. However, recent advances in technology have made it possible to go even further in pursuit of efficient design. Great white sharks can swim at speeds up to 25 miles per hour, mainly because of small scales on their skin called “denticles ” that decrease drag and turbulence. Envious professional swimmers and innovative scientists mimicked the design of these denticles to develop a shark-inspired swimsuit , proven to make swimmers sleeker and less resistant in the water.

An Australian company called BioPower Systems even designed a device resembling a shark’s tail to capture wave energy from the ocean and convert it into electric power. As the world looks for clean energy alternatives to fossil fuels, this kind of technology could be one promising solution.

5. Sharks boost local economies.

Over the last several decades, public fascination with sharks has developed into a thriving ecotourism industry in places such as the Bahamas, South Africa and the Galápagos Islands.

According to a study published in 2013, shark tourism generates more than US$ 300 million a year and is predicted to more than double in the next 20 years. In Australia, shark diving tourism contributes more than US$17.7 million annually to the regional economy. These activities support local businesses (boat rental and diving companies, for example) and provide more than 10,000 jobs in 29 countries. Several studies have indicated that in these places, sharks are worth much more alive than dead. (conservation.org, article by Molly Bergen).

Sharks in The Media

Any discussion would not be complete without the effect of media on sharks, and I will wrap up my discussion with safety in the water. Without a doubt the most famous movie about sharks is the movie Jaws. It was the first summer blockbuster, and millions of viewers were frightened out of their seats. Even Peter Benchley, the author of the best selling book and consultant for the movie admits that if he knew the adverse affect his book and movie had on sharks, he would have never entered in the project. He spent the rest of his life trying to undo the damage that Jaws caused. The book was loosely based on a real incident in 1916 when a great white attacked swimmers along the coast of New Jersey.

“A collective testosterone rush certainly swept through the east coast of the US,” says George Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research in Gainesville. “Thousands of fishers set out to catch trophy sharks after seeing Jaws,” he says. “It was good blue collar fishing. You didn’t have to have a fancy boat or gear – an average Joe could catch big fish, and there was no remorse, since there was this mindset that they were man-killers.” Burgess suggests the number of large sharks fell by 50% along the eastern seaboard of North America in the years following the release of Jaws. And research by biologist Dr Julia Baum suggests that between 1986 and 2000, in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, there was a population decline of 89% in hammerhead sharks, 79% in great white sharks and 65% in tiger sharks. But since the 1990s, protection for great whites has been established in many parts of the world including California, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. This has helped numbers recover somewhat, but there is a long way to go to return to pre-1975 levels.

A new batch of Shark movies come out every decade or so. Sharks make good action stars. Some movies are more accurate than others. Open water was pretty accurate. Some like megalodon are very far fetched, but are fun to watch. Our biggest threat is from shark finning now. Thank the Chinese’s taste for shark fin soup for this assault on the species. Most people have a better understanding of sharks than they did in the 70s.

This article was stimulated by a resurgence in shark attacks in Maine and New York. Great White sharks are in the news again. The problem with great white sharks is that they are very big and dangerous, and most people don’t survive from attacks by great whites. One bite by them usually causes the victim to bleed out and die from hypovolemic shock. White sharks’ favorite food are seals. Due to restrictions and conservation efforts for seal has caused an increase in the seal population which is consequently responsible for the increase in shark spotting. Sharks tend to attack sick seals. The water is cold in the northern states. So people are wearing wet suits. Even Michael Phelps looks clumsy in the water in comparison to seals. So humans in wet suits look like weakened seals. So how do we protect ourselves while in the water, besides staying on the shore? Wearing a light colored wet suit might help. Some sharks can be territorial, but none are actively seeking out humans.”

Safe Practices for Swimming with Sharks

- Practice shark-safe Swimming Habits, it’s always best to swim with a buddy, stay close to shore. Don’t enter the water while bleeding, and use caution near sandbars or steep drop-offs.Avoid swimming at dawn or dusk.

- Look for signs of sharks, Murky water, if sharks can’t see clearly, they are more likely to mistake a person for prey; Bait Fish, avoid beaches with fisherman. And look for signs of bait fish.

- What if you see a shark? First keep an eye on it, but leave the water quickly. You should only hit a shark if you are attacked. Aim for the nose and do it vigorously.

- Remember How Rare Shark Bites Are. This will help you feel less anxious about visiting the beach.

- Think about Your Real Risks. The most life-threatening risk in the water isn’t sharks–it’s the water itself.

Please remember, that the ocean is their home. They don’t bother us on the land. They are dangerous, so please respect them. We are the dominate species on the earth, so we are responsible for conservation. The shark is probably the closest thing we have to a perfect predator. They have evolved to handle every ecological event and as a result have been around for over 400 million years. We as a species have only been on the earth around a 100,000 years. And our early start was poor in comparison. We already know our future if the oceans die, and we know that the shark is an integral part of that ecosystem. We need to think of long term benefits and not short term gain. Besides shark fins are simply cartilage, a ready supply is available at all slaughter houses. They would never know the difference in their soup.

New Shark Facts

Group Activity in Sharks:

(Updated 10/8/2020)

I came across some interesting facts when I watched Shark Week, I am still watching all the show s I taped during that week. In this episode they studied groups of sharks. The Scalloped Hammerhead Shark, the Whale Shark, The Lemon Shark and the White Tipped Reef Shark were studied. They found out that there sharks are capable of learning tasks. They found that a lemon shark could associate an activity like pushing on a metal plate to dispense food. It took the shark a week to figure it out, But once he did, it was a regular activity. When they added a second untrained lemon shark, that shark after spending a day, in what can only be termed studying, was able to replicate the same behavior. So not only can they learn behavior, they can learn from each other.

In the white tip reef sharks, they found that small groups of sharks couple socialize and rest in the day, and work together at night in cooperative hunting techniques. These sharks are also unique that they can rest on the bottom , and circulate water over their gills, so they don’t have to swim constantly in a catatonic state to stay oxygenated and prevent drowning. They tagged several sharks and found out that they maintained relationships for at least the length of the study.

Scalloped Hammerhead sharks and whale sharks migrate vast distances so that they can congregate in large social groups every year. Even younger sharks that have never been to these locations are able to find them. So it is postulated that they must be learning from other sharks.

Apparently many shark species socialize at lest part of their life cycle. Even the loner, the Great White Shark appears to stay in small groups when they are younger. They found two brothers that were still together a year later, and appeared to also cooperatively hunt.

It is more important than ever that we protect sharks, because they are not the dumb brutes that we originally thought they were.

Scared of sharks? This photographer aims to turn shark fear into fascination

A lifelong passion for these ocean predators sparked a career in conservation photography and a mission to share the love.

(Update 6/1/2022)

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHS BYTHOMAS P. PESCHAK

On a miserable day in the middle of winter, I push my then 60-year-old mother into the icy waters of the Atlantic. As a nearby great white shark comes to investigate, my mother faces it, then disappears under the water for what feels like an eternity. She returns to the surface, gasping for breath but smiling. I suppose the galvanized steel cage separating her and the shark had something to do with that.

For as long as I can remember, I have loved sharks and wanted to share that passion with everyone, including my initially reluctant parents. I saw my first shark when I was 16, off Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. A trio of blacktips weaved among barracuda circling above a coral reef. I tried to get closer, finning hard into the open water, but a fierce current held me to the reef. When I showed my underwater photographs of this not-so-close encounter, explaining that the small specks were sharks, I was met with the dubious response: “Of course they are.” From then on, all I wanted was to get closer to sharks.

Left: Light shines into the lagoon of Bassas da India, a remote atoll west of Madagascar, revealing a gathering of juvenile Galápagos sharks. As Peschak descended, the sharks followed him to the coral reef, waltzing in and out of the light.

Right: A whale shark vacuums up a patch of plankton just below snorkeling tourists who come from all over the globe to the Maldives to observe in the wild the world’s largest fish.

After I made the switch from marine biologist to photographer, sharks were my first muses. I have now spent more than two decades documenting their complex and somewhat secretive lives. People often ask me what the most dangerous part of my job is—it’s not swimming with sharks. Statistically the most dangerous things I do are crossing the road, driving my car, and toasting bread. Sharks are not as fearsome as they’re made out to be, but some are formidable predators. Encountering wild sharks in their element is a rare privilege that I treat with equal parts respect, humility, and devotion.

A surfer tests a prototype electromagnetic shark-deterring surfboard alongside a blacktip shark at Aliwal Shoal near Durban, South Africa.

A surfer tests a prototype electromagnetic shark-deterring surfboard alongside a blacktip shark at Aliwal Shoal near Durban, South Africa.

Environmental Postings

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/10/18/why-2-2-doesnt-4-and-an-apple-is-not-an-orange/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/10/17/forest-fires-and-other-natural-disasters-and-their-effect-on-the-environment/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/10/08/sharks-sharks-everywhere-oh-my/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/10/06/natural-selection-and-evolution/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/09/16/our-western-fires/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/09/12/the-creation-of-our-planet-is-a-miracle-and-should-be-cherished/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/06/19/global-warming-and-other-environmental-issues/

https://common-sense-in-america.com/2020/06/12/protecting-our-heritage-saving-endangered-species/