I have written several articles on postings related to Big Tech, Social Media and Corporations. A list of links have been provided at bottom of this article for your convenience. This article will, however address different aspects on these Industries.

A monopoly is a business that is effectively the only provider of a good or service, giving it a tremendous competitive advantage over any other company that tries to provide a similar product or service.

Keep reading to learn more about how monopolies can negatively affect the economy and the rare instances in which the government actually creates them on purpose.

Definition and Examples of a Monopoly

A monopoly is a company that has “monopoly power” in the market for a particular good or service. This means that it has so much power in the market that it’s effectively impossible for any competing businesses to enter the market.

The existence of a monopoly relies on the nature of its business. It is often one that displays one or several of the following qualities:

- Needs to operate under large economies of scale

- Requires huge capital

- Offers a product with no substitute

- Prompts government mandate ensuring its sole existence

- May possess—but does not always possess—technological superiority and control resources

Examples in the U.S.

The most famous monopoly was Standard Oil Company. John D. Rockefeller owned nearly all the oil refineries, which were in Ohio, in the 1890s. His monopoly allowed him to control the price of oil. He bullied the railroad companies to charge him a lower price for transportation. When Ohio threatened legal action to put him out of business, he moved to New Jersey.

In 1998, the U.S. District Court ruled that Microsoft was an illegal monopoly. It had a controlling position as the operating system for personal computers and used this to intimidate a supplier, chipmaker Intel. It also forced computer makers to withhold superior technology. The government ordered Microsoft to share information about its operating system, allowing competitors to develop innovative products using the Windows platform.

But disruptive technologies have done more to erode Microsoft’s monopoly than government action. People are switching to mobile devices, such as tablets and smartphones, and Microsoft’s operating system for those devices has not been popular in the market.

Some would argue that Google has a monopoly on the internet search engine market; people use it for more than 90% of all searches.

How Monopolies Work

Some companies become monopolies through vertical integration; they control the entire supply chain, from production to retail. Others use horizontal integration; they buy up competitors until they are the only ones left.

Once competitors are neutralized and a monopoly has been established, the monopoly can raise prices as much as it wants. If a new competitor tries to enter the market, the monopoly can reduce prices as much as it needs to squeeze out the competitors. Any losses can be recouped with higher prices once competitors have been squeezed out.

U.S. Laws on Monopolies

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act was the first U.S. law designed to prevent monopolies from using their power to gain unfair advantages. Congress enacted it in 1890 when monopolies were known as “trusts,” or groups of companies that would work together to fix prices. The Supreme Court later ruled that companies could work together to restrict trade without violating the Sherman Act, but they couldn’t do so to an “unreasonable” extent.

Some 24 years after the Sherman Act, the U.S. passed two more laws concerning monopolies, the Federal Trade Commission Act, and the Clayton Act. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was established by the former, while the latter specifically outlawed some practices that weren’t addressed by the Sherman Act.

When Monopolies Are Needed

Sometimes a monopoly is necessary. Some, like utilities, enjoy government regulations that award them a market. Governments do this to protect the consumer. A monopoly ensures consistent electricity production and delivery because there aren’t the usual disruptions from free-market forces like competitors.

There may also be high up-front costs that make it difficult for new businesses to compete. It’s very expensive to build new electric plants or dams, so it makes economic sense to allow monopolies to control prices to pay for these costs.

Federal and local governments regulate these industries to protect the consumer. Companies are allowed to set prices to recoup their costs and a reasonable profit.

PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel advocates the benefits of a creative monopoly. That’s a company that is “so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute.” He argues that they give customers more choices “by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world.”

Criticism of Monopolies

Monopolies restrict free trade and prevent the free market from setting prices. That creates the following four adverse effects.

Price Fixing

Since monopolies are lone providers, they can set any price they choose. That’s called price-fixing. They can do this regardless of demand because they know consumers have no choice. It’s especially true when there is inelastic demand for goods and services. That’s when people don’t have a lot of flexibility about the price at which they will purchase the product. Gasoline is an example—if you need to drive a car, you probably can’t wait until you like the price of gas to fill up your tank.

Declining Product Quality

Not only can monopolies raise prices, but they also can supply inferior products. If a grocery store knows that poor residents in the neighborhood have few alternatives, the store may be less concerned with quality.

Loss of Innovation

Monopolies lose any incentive to innovate or provide “new and improved” products. A 2017 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that U.S. businesses have invested less than expected since 2000 in part due to a decline in competition. That was true of cable companies until satellite dishes and online streaming services disrupted their hold on the market.

Inflation

Monopolies create inflation. Since they can set any prices they want, they will raise costs for consumers to increase profit. This is called cost-push inflation. A good example of how this works is the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The 13 oil-exporting countries in OPEC are home to nearly 80% of the world’s proven oil reserves, and they have considerable power to raise or reduce oil prices.

Key Takeaways

- When a company effectively has sole rights to a product’s pricing, distribution, and market, it is a monopoly for that product.

- The advantage of monopolies is the assurance of a consistent supply of a commodity that is too expensive to provide in a competitive market.

- The disadvantages of monopolies include price-fixing, low-quality products, lack of incentive for innovation, and cost-push inflation.

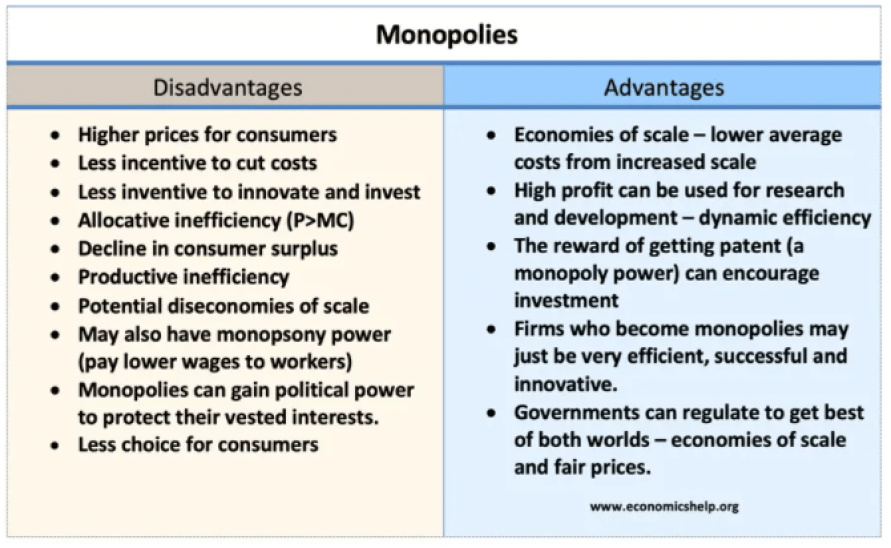

Advantages and disadvantages of monopolies

Monopolies are firms who dominate the market. Either a pure monopoly with 100% market share or a firm with monopoly power (more than 25%) A monopoly tends to set higher prices than a competitive market leading to lower consumer surplus. However, on the other hand, monopolies can benefit from economies of scale leading to lower average costs, which can, in theory, be passed on to consumers.

Disadvantages of monopolies

- Higher prices than in competitive markets – Monopolies face inelastic demand and so can increase prices – giving consumers no alternative. For example, in the 1980s, Microsoft had a monopoly on PC software and charged a high price for Microsoft Office.

- A decline in consumer surplus. Consumers pay higher prices and fewer consumers can afford to buy. This also leads to allocative inefficiency because the price is greater than marginal cost.

- Monopolies have fewer incentives to be efficient. With no competition, a monopoly can make profit without much effort, therefore it can encourage x-inefficiency (organisational slack)

- Possible diseconomies of scale. A big firm may become inefficient because it is harder to coordinate and communicate in a big firm.

- Monopolies often have monopsony power in paying a lower price to suppliers. For example, farmers have complained about the monopsony power of large supermarkets – which means they receive a very low price for products. A monopoly may also have the power to pay lower wages to its workers.

- Monopolies can gain political power and the ability to shape society in an undemocratic and unaccountable way – especially with big IT giants who have such an influence on society and people’s choices. There is a growing concern over the influence of Facebook, Google and Twitter because they influence the diffusion of information in society.

In the late nineteenth-century, large monopolist like Standard Oil gained a notorious reputation for abusing their power and forcing rivals out of business. This led to a backlash against monopolists. But, in the Twenty-First Century, there are new monopolies which have an increasing influence on people’s lives.

Monopoly Diagram

A competitive market produces at Qc and Pc

A competitive market produces at Qc and Pc- A monopoly produces less (Qm) and charges higher price (Pm)

Inefficiency of monopoly

- Monopolies set the price of Pm – which is higher than Pc (allocative inefficiency)

- Monopolies produce at Qm (which is productive inefficient – not the lowest point on AC curve)

- Monopolies lead to deadweight welfare loss of blue triangle

Advantages of monopolies

Monopolies are generally considered to have several disadvantages (higher price, fewer incentives to be efficient e.t.c). However, monopolies can also give benefits, such as – economies of scale, (lower average costs) and a greater ability to fund research and development. In certain circumstances, the advantages of monopolies can outweigh their costs.

- Economies of scale. In an industry with high fixed costs, a single firm can gain lower long-run average costs – through exploiting economies of scale. This is particularly important for firms operating in a natural monopoly (e.g. rail infrastructure, gas network). For example, it would make no sense to have many small companies providing tap water because these small firms would be duplicating investment and infrastructure. The large-scale infrastructure makes it more efficient to just have one firm – a monopoly

Note these economies of scale can easily outweigh productive and allocative inefficiency because they are a greater magnitude. - Innovation. Without patents and monopoly power, drug companies would be unwilling to invest so much in drug research. The monopoly power of patent provides an incentive for firms to develop new technology and knowledge, that can benefit society. Also, monopolies make supernormal profit and this supernormal profit can be used to fund investment which leads to improved technology and dynamic efficiency. For example, large tech monopolies, such as Google and Apple have invested significantly in new technological developments.

- However, this can also have downsides with drug companies able to charge excessively high prices for life-saving drugs. It also gives drug companies an incentive to push pharmaceutical treatments rather than much cheaper solutions to promoting good health and avoiding the poor health in the first place.

- Firms with monopoly power may be the most efficient and dynamic. Firms may gain monopoly power by being better than their rivals. For example, Google has monopoly power on search engines – but can we say Google is an inefficient firm who don’t seek to innovate?

Evaluation of pros and cons of monopolies

- It depends whether market is contestable. A contestable monopoly will face the threat of entry. This threat of entry will create an incentive to be efficient and keep prices low.

- It depends on the ownership structure. Some former nationalised monopolies had inefficiencies, e.g. British Rail was noted for poor sandwich selection and some inefficiencies in running the network. However, this may have been partly monopoly power but also the lack of incentives for a nationalised firm.

- It depends on management. Some large monopolies have successful management to avoid the inertia possible in large monopolies. For example, Amazon has grown by keeping small units of workers who feel a responsibility to compete against other units within the firm.

- It depends on the industry. In an industry like health care, there are different motivations to say banking. Doctors and nurses do not need a competitive market to offer good service, it is part of the job. If we take the banking industry, the economies of scale in offering a national banking network are limited. If it was a merger of two steel firms, which has much higher fixed costs, the economies of scale may be greater.

If two pharmaceutical firms or aeroplane manufacturers merged, there could be a good case to say they would use their combined profit for research and development. - It depends on government regulation. If governments threaten price regulation or regulation of service, this can reduce the excesses of some monopolies.

- Environmental factors – A monopoly which restricts output may ironically improve the environment if it lowers consumption.

- It depends on how you define the industry. A domestic monopoly in steel may still face international competition – from foreign steel companies. Eurotunnel faces a monopoly on trains between the UK and France but it faces competition from other methods of transport – e.g. planes and boats.

Advantages of being a monopoly for a firm

Firms benefit from monopoly power because:

- They can charge higher prices and make more profit than in a competitive market.

- The can benefit from economies of scale – by increasing size they can experience lower average costs – important for industries with high fixed costs and scope for specialisation.

- They can use their monopoly profits to invest in research and development and also build up cash reserves for difficult times.

Why governments may tolerate monopolies

- It is difficult to break up monopolies. The US government passed a lawsuit against Microsoft, suggesting it should be split up into three smaller companies but it was never implemented.

- Governments can implement regulation of Monopolies e.g. OFWAT regulates the prices for water companies. In theory, regulation can enable the best of both worlds – economies of scale, plus fair prices. However, there is concern about whether regulators do a good job – or whether there is regulatory capture with firms gaining generous price controls.

What Effect Does a Monopoly Have on Businesses?

Price Control

Monopolies, being the only company in their specific market, exploit their power and independently set the price of the product or service without having to consider what the competition’s price is. This usually results in higher prices for the consumers (either individuals or businesses) than a market with multiple businesses providing the same service or product. It basically raises the operating costs for all buyers in a monopoly-controlled market.

Supply Control

A monopoly not only has the ability to set a higher price but also can produce less quantity of the product or provide less service. For example, a monopolistic postal service company can provide less choice of letter collection and delivery service for customers, including individuals and businesses with shipping needs, because consumers have no other alternatives from which to choose.

Market Entry Costs

Even if the high prices and low supply of a particular product or service in a monopolized market attracts other businesses, there can be barriers to entry. That’s why the monopoly can exist and maintain its dominance. Entry costs can be high: The set-up of your own business, including technical and financial arrangements in the beginning, can be difficult and expensive. For example, launching a new radio station may require advanced technical apparatus.

Restrictions and Regulations

Legal restrictions, government regulations, patents or franchise rights are also common in a monopolistic market. To enter the market businesses must apply for special rights or undergo specific regulations. These restrictions may require high technical apparatus and incur costs for the businesses.

The Costs of Monopoly: A New View

Contrary to conventional wisdom, monopolies inflict substantial economic harm, particularly on the poor

Economists overwhelmingly agree that the actual costs of monopoly are small, even trivial. This consensus is based on a theory that assumes monopolies are well-run businesses that limit their output in order to drive up prices and maximize profit. And because empirical studies have found that monopolists do not restrict output or raise prices by very much, most economists have concluded that monopolies inflict relatively little harm on the economy.

In this essay, I review recent research that upends both the theoretical and empirical elements of this consensus view. This research shows that monopolies are not well-run businesses, but instead are deeply inefficient. Monopolies do drive up prices, as conventional theory suggests, but because they also reduce productivity, they often ultimately destroy most of an industry’s profits. These productivity losses are a dead weight loss for the economy, and far from trivial.

The new research also shows that monopolists typically increase prices by using political machinery to limit the output of competing products—usually by blocking low-cost substitutes. By limiting supply of these competing products, the monopolist drives up demand for its own. Thus, in contrast to conventional theory, the monopolist actually produces more of its own product than it would in a competitive market, not less. But because production of the substitutes is restricted, total output falls.

The reduction in productivity exacts a toll on all of society. But the blocking of low-cost substitutes particularly harms the poor, who might not be able to afford the monopolist’s product. Thus, monopolies drive the poor out of many markets.

Monopoly theory, old and new

The standard view

In the standard theory of monopoly found in textbooks, the monopolist is a single seller of a good who increases his or her price above competitive levels, leading to reduced output. The key cost of monopoly is the restriction of industry production. Two basic assumptions, or tenets, underlie this theory.

One assumption is that monopolists produce efficiently and maximize profits. This tenet is based on logic, not evidence. Nobel Laureate George Stigler provides one rendition of this logic: “The goal of efficiency is pervasive in economic life, where efficiency means producing and selling goods at the lowest possible cost (and therefore the largest possible profit). This goal is sought as vigorously by monopolists as by competitors”.

Another assumption is that monopolists have close substitutes. This tenet is primarily based on logic, not evidence. Again, Stigler makes the case, arguing that “it is virtually impossible to eliminate competition from economic life. If a firm buys up all of its rivals, new rivals will appear. … If the state gives away monopoly privileges … there will emerge a strong competition in the political area for these plums”.

The consensus view that monopolies inflict little actual damage on society has dominated the economics literature since the seminal work by University of Chicago economist Arnold Harberger. Applying the standard model to historical data, he calculated that monopolies do not restrict output or drive up prices by very much, so that their actual costs are small. This quickly became the accepted view. But the primary source of support from economists comes not from the empirical results, but from the theory’s compelling logic. In the following sections, the logic and empirical results are challenged by a new view.

A new view of monopoly

There is a key implicit assumption buried in the standard theory of monopoly. Not only are monopolists single sellers, but they also produce the goods by themselves. That is, the monopolist (and perhaps clones or mindless automatons) staffs all of the machines, all of the phones, all of the processes involved in producing the good. Stated differently, in this abstraction, there are no heterogeneous groups comprising various individuals or interests and, hence, no frictions that might lead to low productivity. Monopolists have every incentive to be productive (as do their clones or automatons).

When a monopoly forms, it stops competition from the outside. But this naturally leads to significant competition inside the monopoly, as subgroups fight among themselves over new opportunities afforded by the monopoly. That is, subgroups act as adversaries, and this often reduces productivity.

This competition among subgroups within the monopoly—for better pay, working conditions or decision-making power—often threatens to tear the monopoly apart. To survive, the subgroups agree to find ways to limit internal competition. Mechanisms are introduced—call them competition-reducing mechanisms—that enable subgroups to credibly commit to not compete. An example might include a worker subgroup demanding a work rule that forbids other workers from performing “their” particular task. But these mechanisms come at a high cost: reduced productivity. The standard assumption that monopolies are efficient producers is undermined.

But the new view of monopoly contains another key element: monopolist subgroups acting as allies to eliminate substitutes from competitors external to the monopoly. Consider the logic of close substitutes. Politically adept monopolies (as they are de facto since the large majority of monopolies result from special privileges granted by the government) often use their political influence to weaken or destroy existing substitutes for their product. Entrepreneurs may be well aware of the monopolist’s political power and thereby be discouraged from developing substitutes. Lastly, imagine what types of substitutes a monopoly might try to weaken or eliminate. It would not go after those with broad political support. Rather, it would target those with little support, those purchased by politically disadvantaged low-income segments of the population.

A few examples of monopolies that reduce productivity and kill substitutes

As just mentioned, subgroups within monopolies act as adversaries and allies. Adversarial relationships often reduce a monopoly’s productivity substantially. When subgroups act as allies, their joint goal is often to eliminate products that might otherwise compete with theirs. While subgroups in any monopoly engage in both adversarial and cooperative actions, I’ll discuss separate examples of each in this section.

Adversaries: Reducing productivity

I’ll start by looking at some adversarial relationships. In the United States, the sugar cartel, cement industry and construction business provide excellent examples of subgroups within monopolies acting as adversaries and reducing productivity.

The New Deal U.S. sugar cartel

During the Great Depression, the sugar manufacturing industry was one of many industries permitted to form a cartel as part of New Deal economic policy. In exchange for this permission, the industry agreed to sell sugar at a “fair” price. In addition, members of the industry, including factory owners and incumbent farmers, drafted a joint plan (subject to government approval) for how the cartel would meet price targets and share cartel profits. The cartel allocated sales quotas to factories each year so as to hit the agreed-upon price target, a price in line with the agreement with the federal government. This cartel operated from 1934 to 1974.

There were many adversarial relationships within the sugar industry that led to cartel rules beyond the factory sales quotas. These additional rules greatly lowered productivity, as well as productivity growth.

One such example: conflict between farmers and factory owners. Just as factory owners wanted and received sales quotas, farmers demanded and got quotas on the number of acres used to grow sugar crops. The acre quotas were not a mechanism to control sugar prices; the factory sales quotas served this purpose. Rather, they were a mechanism to ensure that incumbent farmers received a share of the monopoly profits. Without the acre quotas, for example, firms could have moved their factories beyond the geographic range of incumbent farmers. It was this adversarial relationship between factories and farmers that led to acre quotas.

Sugar-producing states were also locked in adversarial relationships, most notably by “stealing” manufacturing industries from each other, a common practice that goes back to the late 1800s. So some cartel subgroups, in particular, local and state authorities, had the incentive to push for limits on the renting of quotas, whereby acre quotas could be traded only within counties. Ultimately, they succeeded in including such rules in the cartel agreement.

These cartel rules led to large productivity losses. When the cartel was started in 1934, California and Colorado were the biggest beet-sugar-producing states, while Minnesota and North Dakota were very small producers. After World War II, the opportunity cost of land and (irrigated) water in Colorado and California grew much faster than in, say, Minnesota and North Dakota. Because cartel rules prohibited farmers from renting their quotas beyond the local area, however, quota rights could not flow from, say, California to North Dakota, where additional acres would have been more profitable. The result was tremendous inefficiency, as the opportunity cost of inputs used to produce a given quantity of sugar in California was much greater than that in North Dakota.

The same thing happened where sugar cane was grown. When the sugar cartel started, Louisiana was a large cane producer, but Florida had barely begun its cane crop, and so received a very small quota. After WWII, the profit of the marginal farmer in Florida began growing much faster than that of his or her counterpart in Louisiana but, again, quotas could not move to Florida, where production would have been more profitable.

Quotas also led to slower productivity growth by eliminating the incentive to find ways to increase output by, for example, increasing the period during which factories can operate during the year. Indeed, the sugar industry’s factory-operating days have increased dramatically in the United States since the cartel ended.

The cement industry

The U.S. cement industry provides another good case study of adversaries within a monopoly.

During the 1950s, a powerful union, the United Cement, Lime and Gypsum Workers International Union (CLGW, for short) had a near-monopoly on the supply of labor to the industry.

Again, there were many adversarial relationships among subgroups. One was between different groups of workers. Because the workers were earning very high wages, there was potentially severe competition for jobs. Hence, groups of workers fought for rules that would secure their jobs from competition from other workers. For example, union contracts had rules such as: “When the Finish Grind Department is completely down for repairs, the Company will not use Repairmen assigned to the Clinker Handling Department on repairs in the Finish Grind Department.” No detailed knowledge of cement plants is needed to understand that this rule was meant to protect the repair jobs in the Finish Grind Department.

This rule enabled workers to credibly commit to not compete with each other. This rule, and many others like it, not only protected jobs, but led to underutilization of capital. Such rules led to a waste of resources, like energy. Such mechanisms, sometimes called restrictive work practices, led to significant reductions in industry productivity.

Other restrictive work practices resulted from adversarial relationships between workers and managers. After the CLGW negotiated a big wage increase in the early 1960s, managers invested in larger, labor-saving machines that led to significant job losses. Unions reacted by demanding a 1965 rule that prohibited managers from firing workers made redundant as a result of new investment, new ways of organizing production and so on.

Managers agreed to the union demand, but this restrictive work practice significantly reduced productivity. One would expect this rule to have dulled investment incentives and, indeed, there is evidence of a dip in investment in the late 1960s. But the energy crisis of the 1970s hit the cement industry hard, and the industry responded by making big investments in new, energy-efficient machinery. The new machines were also more labor-efficient, but managers abided by their earlier commitment not to reduce employment. Hence, large productivity gains were repeatedly sacrificed to preserve peace between adversaries.

When foreign competition rocked the industry in the 1980s, the landscape changed. Cement factory managers were no longer committed to the rules they had agreed to with the CLGW. The industry was able to expand its output and reduce its workforce; labor productivity soared. The gains that were missed in the 1970s were enjoyed in the 1980s.

Construction: Size is not the issue

Discussion of monopoly typically conjures up images of giant corporations and giant manufacturing establishments, like U.S. Steel and its massive factories. But, in fact, the size of the monopolist’s operation does not correlate with its destructive impact. Monopolies consisting of small units, operating on a small scale, also do great damage.

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis found this to be true 90 years ago in dealing with the Chicago construction industry. He described an industry in turmoil:

“It is the violation of no confidence to say that building construction has gotten into bad repute in this community. There was a general disposition to keep away from it as a thing diseased. Capital avoided it. The wise dollar preferred almost any other form of activity or no activity”.

To address these serious problems in Chicago construction, Landis was appointed to arbitrate wage disputes. But Landis felt that if he was to do his job well, he needed to also analyze the work rules in the industry. This surprised and scared most of the parties involved. Landis also knew that the work rules contained in the contracts were the tip of the iceberg, so he spent a considerable amount of time going out to jobs, talking with the workers and investigating the situation firsthand. He concluded that while high wages were an is

“The real malady lurked in a maze of conditions artificially created to give parties a monopoly, and in rules designed to produce waste for the mere sake of waste; all combined to bring about an insufferable situation, not the least burdensome element of which was the jurisdictional dispute between trade-union members of the same parent organization”.

The waste he reported is with us still.

Allies: Eliminating substitutes

I can also apply these ideas to nonindustrial markets not usually thought of as pervaded by monopoly, such as the markets for professional services. Although these markets are made up of thousands of independent professionals, these professionals band together to act as a cartel, a monopoly composed of many separate business entities. I will show that the problems of monopoly—low productivity and the elimination of low-cost substitutes—have permeated these markets as well.

Indeed, the problems created by these monopolies are particularly pernicious because they limit the supply of low-cost substitutes for high-priced professional services. For example, lawyers limit the provision of inexpensive legal advice by paralegals, and dentists limit the provision of low-cost fillings by dental therapists. These limitations are not too harmful to the rich. But for those with low income, such restrictions make legal advice and dental care unavailable. They are priced out of the market. Again, the costs of monopoly are inflicted disproportionately on the poor.

Subgroups in a monopoly are not necessarily adversaries. Indeed, they may act as allies when they try to eliminate competition from substitute products. Consider, for example, the dental industry. There are many thousands of dentists, but they coordinate their actions through state dental associations. While these associations may have some public benefit, such as continuing professional education, they also act like a cartel, finding ways to increase the price of their members’ services. They do so in a way that also increases the demand for their services.

One service dentists provide is filling cavities. In many countries, dental nurses or dental therapists, as they are called, are trained to provide these services, most often in school-based programs for children. In the United States, dental therapists have been vigorously opposed by dentists, with a few exceptions, including the native villages of Alaska and the state of Minnesota.

The impact of these cartel restrictions is profound. Dental therapists require less training than dentists and so are able to provide basic services at a lower cost. Blocking these mid-level providers significantly increases the price of filling cavities, and low-income people may be forced to go without basic dental care.

The debate over dental therapists in the United States is not over. Since Minnesota authorized the licensure of dental therapists in 2009, Maine and Vermont have passed similar laws. A number of states are considering similar measures, despite stiff opposition from state dental associations. The laws often require that dental therapists work under the direct supervision of dentists, ostensibly for the protection of patients, but the arrangement also protects dentists from competing directly with dental therapists operating independently.

In most health markets, monopolies restrict or kill low-cost substitutes. For example, in the hearing aid industry, audiologists, who have Ph.D.s, often put tremendous entry restrictions on hearing aid fitters. The fitters are less skilled, but are perfectly capable of most work. Again, the poor are hurt by this.

This same analysis applies to many other types of services. Lawyers introduce statutes to prevent the “unlawful practice of law.” Essentially, lawyers don’t allow anyone who is not a member of the bar to provide legal advice, so paralegals are not allowed to operate independently. Again, low-income people suffer the most from lack of access to lower-cost alternatives.

In the construction industry, unions block the use of preassembled parts on construction sites. This eliminates a close substitute: factory assembly. Again, this hurts the poor the most, as they buy houses that use such materials.

Schmitz provides many more industries and much more analysis.

Adversaries and allies: Low productivity, few substitutes

U.S. Steel is often cited as a classic example of a monopoly. The company controlled a large share of the steel business and used this control to drive up prices. But it is also a good example of the new theory, illustrating the bigger picture of the costs its monopoly imposes on the economy. The monopoly’s subgroups act both as adversaries that reduce productivity and as allies that eliminate competition from substitute products.

The U.S. Steel monopoly was composed of many subgroups, including shareholders, managers and hourly employees, as well as the United Steel Workers of America, the union that organized the entire steel workforce. I’ll sometimes refer to the monopoly as the USS-USW monopoly.

In some settings, these groups were fierce adversaries. In others, they were strong allies. Consider their adversarial roles. Given that the monopoly was generating significant profits, at least at first, subgroups had an incentive to increase their share of the pie and certainly to protect their share from other subgroups. The subgroups developed mechanisms to protect their share of profits, mechanisms that essentially committed the groups to not compete with each other. Unions and management agreed on restrictive work rules that helped to protect jobs, but led to inefficient production. Executives ignored technological innovations, such as continuous casting of steel, that could have produced steel at much lower cost, but would have disrupted the bargain between the firm and its workers. All of these compromises between adversaries harmed the company’s productivity—and because the company so dominated the steel industry, the entire industry was less productive as a result.

Next consider the subgroups in their roles as allies. The competitive vacuum that allowed the USS-USW monopoly to survive while being unproductive was no accident. Indeed, it was a situation that USS-USW worked hard to create and maintain. The issue is not merely that U.S. Steel bought up and maintained control of competing steel companies within the United States, as monopolists always do, or that the USW successfully organized the entire steel workforce. If subgroups USS and USW had done only those two things, they still would have faced significant competition from foreign firms—competition that would have forced them to raise productivity and take on new, better technology. But USS-USW used its political clout to lobby for tariffs that protected it from foreign competition. That is, U.S. Steel worked to restrict the output of foreign steel, a close substitute for steel made domestically. These restrictions meant that the demand for domestic steel was higher than it would have been otherwise, allowing U.S. Steel to increase its output, even as it increased prices. These artificially inflated prices injured any U.S. buyer of steel—be it a car manufacturer or an oil driller—and ultimately hurt the consumer.

Summary and conclusion

For decades, the theoretical understanding and empirical analysis of monopoly have themselves been monopolized by a dominant paradigm—that the costs of monopoly are trivial. This blindness to new theory and analysis has impeded economists’ understanding of the actual harm caused by monopoly. Rather than inflicting little actual damage, adversarial relationships within monopolies have significantly reduced productivity and economic welfare. And in many industries, subgroups within monopolies collaborate to eliminate competition from low-cost substitutes. This lack of competition in the marketplace has a disproportionate impact on poor citizens who might otherwise find low-cost services that would meet their needs.

I’ve described this as a “new” theory, but in truth its roots go back decades, to the ideas of Thurman Arnold. Arnold ran the Antitrust Division at the Department of Justice from 1938 to 1943, taking aim at a broad range of targets, from automakers to Hollywood movie producers to the American Medical Association. He argued that lack of competition reduced productivity and that monopolies crushed low-cost substitutes, hurting the poor. Arnold supported his arguments through intensive real-world research. He and his staff undertook detailed investigations of monopolies, examining the on-site operations of many industries and documenting the productivity losses and destruction of substitutes caused by monopoly.

Arnold began his work at a pivotal time—in the midst of the Great Depression, just after the United States had experimented with the cartelization of its economy. Faith in competitive markets had reached such a low that cartels and monopolies were thought to be, perhaps, better alternatives. His work and ideas played a big role in reinvigorating confidence in competitive markets. He mounted an aggressive campaign to protect society from monopoly. The campaign had two parts: forceful prosecution of monopoly through the courts, accompanied by an array of speeches and articles to educate the general public about its costs.

Economists gradually forgot Arnold and his ideas, convinced by Harberger’s empirical work and the introspection of economists, leading to, for example, the logic provided by Stigler and others. Scholars and regulators who studied monopolies focused on prices alone and found little to worry about.

But as shown by the research reviewed in this essay—and an expanding body of empirical work—the problems caused by monopoly are significant, and still pervasive. It is with Hope that this article will open a new era of discussion about monopoly and its costs, and ultimately lead policymakers to encourage greater competition for the benefit of all.

Resources

thebalance.com, “What Is a Monopoly?,” By Kimberly Amadeo; economicshelp.org, “Advantages and disadvantages of monopolies,” By Tejvan Pettinger;process.st, “Why Are Monopolies Bad? An Analysis of 6 Rise-and-Fall Companies,” By Adam Henshall; investopedia.com, “How and Why Companies Become Monopolies,” By James McWhinney; huffpost.com, “How Media Monopolies Are Undermining Democracy and Threatening Net Neutrality,” By Robert Scheer; theatlantic.com, “How Corporate Lobbyists Conquered American Democracy: Business didn’t always have so much power in Washington.” By Lee Drutman; minneapolisfed.org, “The Costs of Monopoly: A New View: Contrary to conventional wisdom, monopolies inflict substantial economic harm, particularly on the poor,” By James A. Schmitz, Jr.;

Addendum

Why Are Monopolies Bad? An Analysis of 6 Rise-and-Fall Companies

When I think of monopoly I think of a mustachioed man with a nice hat and a highland terrier.

When I think of monopoly I think of a mustachioed man with a nice hat and a highland terrier.

I also think of family arguments and Christmas flashbacks; Monopole mon amour, directed by Resnais…

Yet, those aren’t the only monopoly connotations you should be worried about. The New York Times recently reported that a whopping 77% of mobile social traffic is owned by Facebook, 74% of the ebook market is Amazon, and Google owns 88% percent of the search advertising market.

They aren’t the only monopolies around and they’re only in specific sectors. A report from eMarketer showed that in 2016 Facebook and Google collectively accounted for 57% of all mobile advertising – and that figure is rising. Maybe it’s not a monopoly at all, but a duopoly?

Market position isn’t static, it’s dynamic. Monopolies form and fade, doing so in response to specific factors and environments.

In this article, we’ll look at the rise and fall of some monopolistic scenarios and try to learn a little about how this current dominance may look moving forward.

History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as AOL

East India Trading Companies and the birth of corporate monopolies

One of the first widely known examples of monopolies may be that of the trading companies established as quasi-feudalist mercantilism began to transition closer to what we might consider early manifestations of capitalism.

(Finally managed to make use of my degrees…)

This was the birth of empire and the global expansion was delivered largely through the competition of private forces. The East India Company (EIC) was the British wing of this venture and, at its largest, its operations amounted to half the world’s trade. It traded in cotton, silk, salt, tea, opium, and much more. The company ruled much of India until 1858 when the British government stepped in and established the Raj.

What we see in the East India Company is a business established during a period of broader social change. The legal foundations which enabled capitalist modes of exchange had been formed in Germanic states and the codification of laws and legal practices was beginning to occur across northern Europe.

The printing press had been invented by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440, only 160 years before the EIC received its Royal Charter. Europe was going through an information revolution; albeit, a much slower one than we’re enjoying now.

According to Professor Jeremiah Dittmar of the London School of Economics, writing in 2011, European cities which adopted the printing press experienced 60% higher economic growth than those which didn’t buy into the technology from 1450 to 1600. Ironically, in the context of this article, the printing press itself was monopolistic as the knowledge of materials was quasi-proprietary:

According to Professor Jeremiah Dittmar of the London School of Economics, writing in 2011, European cities which adopted the printing press experienced 60% higher economic growth than those which didn’t buy into the technology from 1450 to 1600. Ironically, in the context of this article, the printing press itself was monopolistic as the knowledge of materials was quasi-proprietary:

The first known “blueprint” manual on the production of movable type was only printed in 1540. Over the period 1450-1500, the master printers who established presses in cities across Europe were overwhelmingly German. Most had either been apprentices of Gutenberg and his partners in Mainz or had learned from former apprentices.

The point is that the East India Company was entering new waters, both literally and figuratively.

It was built on technological and social advancements and being the first big player on the scene. It was helped by being granted a legal monopoly from the outset, but it had competition to face too.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded in 1602 and was awarded a 21-year Dutch monopoly from the outset. There are some, including Timothy Brook and Bryan Taylor, who would argue the VOC were the most successful company ever to exist. Though the two, VOC and EIC, held multiple monopolies between them, neither completely outstripped the other.

A duopoly was held.

Ultimately, the EIC was to lose its privileged position. The company was now in some financial difficulty and after the Indian Rebellion of 1857 the British government nationalized the company, absorbed its army, and gradually wound down its operations until 1874.

The monopolies collapsed due to a changing market, unsustainable growth, and state intervention.

Keep this in mind.

The rise-and-falls in the information age

IBM, the first real tech company

IBM was one of the first tech monopolies within what we now consider to be the tech space. Founded in 1911 and named IBM in 1924, it had a solid hold on expertise and market share for most of the twentieth century.

IBM was one of the first tech monopolies within what we now consider to be the tech space. Founded in 1911 and named IBM in 1924, it had a solid hold on expertise and market share for most of the twentieth century.

IBM came up with so many of the technologies which we now take for granted. The first commercially available modern computers were thanks to the research and development undertaken within the company. IBM even launched the first smartphone – without commercial success. The ability to be ahead of the curve innovation-wise meant that not only did IBM lead the pack, but other companies were reliant on the services or hardware it offered.

Despite all this success, IBM no longer has a monopolistic position in the market. That’s not to say they’re not doing well – $80 billion in revenue is no small number. Yet, IBM now makes up one of many businesses operating in the specific sectors it fills. More than that, there are worrying signs as IBMs revenue has declined for the 20th consecutive quarter.

The success of IBM was first threatened when other companies began entering into their turf, making hardware which could compete with IBM – particularly aiming that hardware at the consumer market. This failure to engage the consumer is reflected even further in how IBM lagged behind with the rapid expansion of the internet. IBM lost out recently to Amazon for a CIA cloud computing contract worth $600 million, even though IBM’s proposal was 30% cheaper. It turned out that the IBM proposal was simply significantly worse than Amazon’s pitch.

IBM hasn’t collapsed, by any means. But it lost its dominance in line with significant trends:

- The first on the scene won’t hold its market share forever

- New markets open up and others are faster to exploit this

- The internal organization becomes difficult to negotiate

On this last point, it’s worth mentioning IBM’s Roadmap 2015 – dubbed Roadkill 2015 by employees – which was geared according to Businessweek to benefit short-term shareholder returns at the expense of staff and long term success with customers.

According to Steve Denning, from the Forbes article linked above:

The real challenge for the CEO of IBM is a fundamental shift in business goals and culture. Instead of a world where a high-pressure sales teams can lock in customers to long-term contracts for using unchanging software with high margins, now IT services providers have to compete with firms that offer continuous innovation, pay-as-you-go fee structures and freedom to exit any time. To compete successfully in this emerging world, the IT service providers will have to delight their customers on a continuing basis, by offering continuous innovation.

The old fashioned corporate business model which led IBM to success in the twentieth and early twenty-first century is no longer what customers are looking for. IBM’s delivery of corporate and small business software was disrupted partly by the innovative practices and models of cloud-based startups in that scene.

John Wookey from Salesforce told the New York Times:

The economics are different, but what is really different is the relationship with the consumer. We issue a new version of the product every four months. If the customer doesn’t like it, he stops paying.

Technological innovations like cloud computing and the availability of powerful hardware to all opened up space in the market for companies to offer greater flexibility to their customers’ needs. Add to this the fact that startups are generally significantly more agile than large businesses, who have to pass every change and proposal through multiple boards of managers and executives, then you end up compounding the impact of this flexibility.

As Denning put in 2014:

Established firms like IBM are used to operating in a world where new versions of packaged software come out every few years, making it difficult to get out of a license when company data depends on it. The emerging world of cloud computing will require much greater agility.

Wookey’s Salesforce now has a revenue of $8.39 billion – over a 100% increase on their 2014 figures.

We’ll leave IBM and Salesforce with this quote to bear in mind from Wookey:

The hardest thing is to be successful again when you’ve been successful in the old world

AOL probably gave away more free CDs than anyone in history

AOL is still a household name, but there are likely many Millennials now entering the workforce whose only reference point is the late nineties rom-com You’ve Got Mail – which, surprisingly, has aged better than AOL.

It isn’t really fair to single out AOL alone without looking at the battle which raged afterward. AOL was the center of the internet. It provided the search and emailing capacities that so many relied on. Unfortunately for AOL, the pioneer will eventually lose its dominance.

AOL’s most powerful moment probably came in November 1998 when they bought the most popular browser of the time: Netscape. AOL was integrated into so much of internet life and everyone I know has clear memories of throwing away those free CDs they gave out.

Sadly, for the tech pioneer, the merger with TimeWarner proved to be a fairly unsuccessful move and was followed up with the dot-com crash which saw the company stock plummet from $226 billion to a paltry $20 billion – a pauper’s figure.

With an inability to recover, we see a few similar steps typical of a dying star:

- Massive staff cuts and relocation

- CEOs are replaced in relatively quick succession

- Acquisitions are attempted and prove unsuccessful – AOL bought Bebo in 2006 for $850 million. Awkward.

However, there are some glimmers of hope for AOL. In 2013, the Wall Street Journal reported AOL had seen its first quarterly growth figures in 8 years as it tried to push its way into the online advertising arena. Verizon bought AOL in 2015 for $4.4 billion in cash. A monumental fall from $226 billion grace.

The decline of AOL can ultimately be put down to similar factors to IBM. The key, according to Christina Warren, was the arrival of broadband. This technological advancement meant that faster internet was available – plus, it got rid of the whole modem screeching thing, which I still believe should be given more credit than it normally is.

With AOL no longer being the only route into the internet for so many customers, the market opened up and consumers had more choices presented to them. AOL’s dominance and focus on being an ISP rather than a provider of consumer services meant small competitors were able to step in and sweep up new users.

The agile customer facing companies who focused on providing search and mail capabilities had a field day. AOL lost significant market share to both Google and Yahoo, leaving the two to fight it out amongst themselves for the advantage.

Which brings us to an interesting question. We’ve seen some examples so far of why monopolistic companies fail, but not clear examples of how other companies step in to take their place.

Wookey attached Salesforce’s successes to modern software practices – iterations and regular deployment, customer facing attitude, and a focus on flexibility. But much of these philosophies can be tracked back to the post-AOL fight for the internet.

How did Google beat Yahoo and what can we learn from this?

Mohit Aron, an ex-Google employee writing for TechCrunch, looks at the technological infrastructure behind the two companies to give an insight into considerations you have to make within a business to be able to manage scalability is an effective manner.

Yahoo’s system was based on NetApp filers, a third party system which allowed them to expand rapidly – adding new features and meeting customer demand. Alternatively, Google started work on what came to be known as the Google File System. This was an internal project to define the infrastructure of the company and have a solid base to work from.

The results of these differences were that Yahoo was able to meet immediate demand faster and expand rapidly, but that its services were less stable and reliant increasingly on third parties – which became expensive the more expansion occurred. Google, on the other hand, had to be a little slower in releasing new features at first, but this forced them to hone and refine the core features they did have. Then, once the architecture was in place, Google was able to accelerate forward and release more features more quickly than Yahoo with lower relative overhead costs and greater stability through the consistency across the company.

According to Aron:

I believe the lessons here extend beyond infrastructure or application engineering, and offer insight into what it takes to build a sustainable business. It speaks directly to one of the most important things I’ve learned from my time at Google: the need to completely understand the problem before even considering the solution.

It was Google’s long term vision and understanding of what they needed to do which gave them the advantage over Yahoo. The greater infrastructure is merely a symptom of that difference. One could say the classic UX and UI of Google is a symptom of that too. There was a clarity surrounding Google.

So, AOL lost out because they were on the wrong end of a technological shift. Their market dominance proved largely meaningless once the area changed.

New companies were able to exploit this niche by being agile and riding the technological wave.

The company which exploited this most of all was Google, as it had a clear sense of direction and implemented long-term planning from the outset.

The pros and cons of monopolies; pass Go, receive $200?

Monopolies are not necessarily 100% bad in and of themselves.

When a firm like Facebook comes to a position of dominance so quickly, it is quite clear that they are offering a service which solves a problem for the user; it adds clear value.

However, the long-term effects of monopolies, almost regardless of how we might personally feel about the specific company in question, are often negative. Though, they can have positives too.

Leonard E. Read, writing for The Atlantic in 1924 and published now for the FEE lays out some of the typical considerations of monopolies and their effects on the market and the consumers.

There are two ways to attain an exclusive position in the market, that is to say, there are two ways to achieve monopoly. One way is not only harmless—indeed, it is beneficial; the other is bad. The beneficial way is to become superior to everyone else in providing some good or service. The bad way is to use coercive force to keep others from competing effectively and also from challenging one’s position. Rise above others by excellence, or hold others down by coercive force!

Consider my Facebook example given above. I credit Facebook with gaining dominance by providing a good service, but I overlook their expanded market share which is partly due to the acquisition of Instagram and Whatsapp. These business tactics are not somehow avoided in the world of tech; businesses act like businesses even if the CEO wears a t-shirt.

Reaching a dominant market position large enough to be considered monopolistic simply through providing a better service than competitors doesn’t have too many immediate concerns attached to it. However, as companies grow and mature they don’t always stay exactly the same. We shouldn’t trust in a company to act nicely simply because we like their product. Their motivations will be business ones like any other.

Mark Thoma, reporting on Google’s negotiations with European regulators in 2014 for CBS’s Moneywatch, writes:

When firms have such power, they charge prices that are higher than can be justified based upon the costs of production, prices that are higher than they would be if the market was more competitive. With higher prices, consumers will demand less quantity, and hence the quantity produced and consumed will be lower than it would be under a more competitive market structure.

The bottom line is that when companies have a monopoly, prices are too high and production is too low. There’s an inefficient allocation of resources.

These simple economic stances generally ring true whether the company in question is a big data tech giant or a trading company with its own private army. Monopolies are generally not good for the consumer, even though they can present benefits.

One could take a narrative view of this, given our historical approach, and suggest that individual moments of monopoly are bad for the consumer but the continual competition and rise-and-falls creates a long term process which can prove beneficial.

Maybe a monopoly is not too bad as long as there’s a chance it can fail?

You can make your own mind up.

Innovation, disruption, and you

If there is a chance a monopoly can fail then it is reliant on some form innovation or disruption as we’ve seen from our historical examples. Who will rise up next is largely defined by their relation to these factors also.

Ex-Paypal and now Palantir head honcho Peter Theil has stated that he doesn’t like the use of the term disruption, stating:

Disruption has recently transmogrified into a self-congratulatory buzzword for anything trendy and new. This seemingly trivial fad matters because it distorts an entrepreneur’s self-understanding in an inherently competitive way

For Theil, a product shouldn’t simply be cheaper than its competitor, possibly through some shady business practice or “innovative” business model – however you wish to phrase it. Companies which become monopolies have to start off with something which holds true to the original feeling around the word disruption.

They must identify a need which isn’t being served or a need which could be served in a better way, not simply cheaper. For Thiel, that is the cornerstone of innovation and that is what you must start with to build a monopoly.

Because, arguably, the only way to really beat monopolies is to build them.

Counterintuitive, I know.

Peter Thiel has 4 key takeways to consider to try to build a mini-monopoly for your niche:

- Start small and focus on the niche of your niche. Really focus your concept and your direction to do something really well.

- Gradually grow by expanding your services and options one by one through iterations, like how Amazon added CDs alongside books.

- Going head-to-head with competitors is not always recommended – try to do something a bit different and have a real creative difference between the two of you.

- Have a long term plan and know where you want to be in a few years time. Being the first to market doesn’t guarantee long-term success. As our Google vs Yahoo battle demonstrated.

These monopolies are growing. Should we be worried?

Columbia Law Professor Tim Wu suggests that we shouldn’t be quite as worried about monopolies in the internet age because they can be beaten. One of the defining elements of this is the half life of domination. As Erick Shonfeld put it in 2010:

AT&T ruled for 70 years, Microsoft ruled for maybe 25, so far Google has ruled for 10. Will Facebook rule next, and of so, for how long?

Seven years later and our data in the introduction to this article shows that Facebook is playing a much larger role within the industry than it was previously and has the social element of the industry cornered.

As Tim Wu phrases the argument:

Are today’s internet monopolies really comparable to the info monopolies of other ages, like AT&T, the Hollywood studios, and NBC? Informed by the apostle of creative destruction Joseph Schumpeter, some agree that Internet monopolies are inevitable, but insists also that they are also inherently vulnerable and ephemeral. Just wait and today’s monopolies will be reshaped or destroyed by disruptive market forces. Bing may have had a slow start, but it may still run over Google, and if not, perhaps the rise of mobile Apps will make search engines irrelevant altogether. The theory is based, in part, on an inescapable truth: all things change.

Bing lol.

But there are serious points in here too.

- The barriers to entry within digital technologies are lower than at any point in the past, particularly relative to attainable market reach.

- Major technological shifts and advancements are occurring at shorter intervals. What if virtual or augmented reality accelerates in the next decade and suddenly a whole new market opens up which new firms find success in?

It’s difficult. The Economist published an article in May 2017 arguing for greater anti-Trust rules regarding tech giants. The article postulates that data is the new oil. But it comes to a worrying conclusion. That the expanding nature of networks adds to the overall amount of available data isn’t a new idea, but when viewed through the prism of monopolies it makes for very sobering reading.

If Google or Facebook are able to gather more data by orders of magnitude than their competitors while also holding on to the users through usage and engagement with their products, their ability to advertise and do so effectively and cheaply destroys competitors within the field. Every step ahead of the competition accelerates their advantage; like the Amazon Flywheel concept we’ve discussed before in our article on the delivery process.

As such, the Economist argue for authorities to take into consideration more than just company size when assessing mergers, to take into consideration the data assets held by each company. They argue, for instance, that Facebook’s willingness to pay $19 billion for Whatsapp despite a lack of revenue should have been a major red flag.

The second measure the Economist argue for is greater transparency of data. This could be as simple as allowing consumers to see what data is held, how it’s used, and how much money is being made from it. Or, it could be the more radical solution of beginning to see data as a public utility and having a shared collection of data which companies can use and draw from – subject to guidelines and such.

The initial suggestion is a classic step to stop monopolies and simply reflects an updating of traditional systems. The discussions about data management, however, provide a lot more to reflect on and imagine. The designation of data as a public utility would destroy the systemic monopolistic advantage of the Facebooks and Googles of now and in the future.

Games of Monopoly come to an end, even if it feels like forever

Our best way to challenge these monopolies then is to encourage startups to become better, be prepared to break new technological boundaries and to consider how legislation can impact on the way monopolies are formed and perpetuate.

If I’m putting my free-market hat on, I’d be advocating for greater competition to disrupt this concentration of power and market share.

But also, it’s needed to keep pushing and supporting those infrastructural elements which enable startups to form and to emerge in the market as potential players. As Paul Graham makes clear, it isn’t a coincidence that Silicon Valley has been a continual producer of top tech firms. An environment has been constructed there which is beneficial for the growth of companies – particularly those which aim to do something different. In doing so, this draws the right people necessary to come together, mix, and give birth to exciting new concepts and products.

From educational systems to government investment schemes, there is a range of things which can help lay down the grounding upon which these environments can grow and flourish.

Monopolies aren’t bad in and of themselves. But if monopolies don’t come to and end then it’s a sign of a lack of innovation, growth, and progress.

How and Why Companies Become Monopolies

How to Create a Monopoly

There are many ways to create a monopoly, and most of them rely on some form of assistance from the government. Perhaps the easiest way to become a monopoly is by the government granting a company exclusive rights to provide goods or services.

The British East India Company, to which the British government granted exclusive rights to import goods to Britain from India in 1600, may be one of the best-known monopolies created in this manner. At the height of its power, the firm served as the virtual ruler of India with the power to levy taxes and direct armed forces.

In a similar manner, nationalization (a process by which the government itself takes control over a business or industry) is another way to create a monopoly. Mail delivery and childhood education are two services that have been nationalized in many countries. Communist countries often take nationalization to its most extreme, with the government controlling almost all means of production.

Copyrights and patents are another way in which assistance from the government can be used to create a monopoly or a near-monopoly. Because the government has laws in place to protect intellectual property, the creators of that property are given monopoly power over things like ideas, concepts, designs, storylines, songs, or even short melodies.

A good example of this comes from the world of technology, where Microsoft Corp’s (MSFT) copyright of its Windows software effectively gave the firm a monopoly on what amounted to a revolutionary new way for computer users to navigate and manage their on-screen activities.

Having access to a scarce resource is another way to create a monopoly. This is the path taken by Standard Oil under the leadership of John D. Rockefeller. Through relentless and ruthless business practices, Rockefeller took control of over 90% of the oil pipelines and refineries in the United States.1

While the government eventually broke up the monopoly, it took several tries and nearly 20 years to do so. Chevron Corporation (CVX), Exxon Mobil Corp. (XOM), and ConocoPhillips Co. (COP) are all legacy companies resulting from the breakup of that monopoly. De Beers Consolidated Mines Limited also used access to a scarce resource—diamonds—to create a monopoly.

Mergers and acquisitions are another way to create a monopoly or a near-monopoly even in the absence of a scarce resource. In such cases, economies of scale create economic efficiencies that allow companies to drive down prices to a point where competitors simply cannot survive.

Why Monopolies Are Created

While governments usually try to prevent monopolies, in certain situations, they encourage or even create monopolies themselves. In many cases, government-created monopolies are intended to result in economies of scale that benefit consumers by keeping costs down.

Utility companies that provide water, natural gas, or electricity are all examples of entities designed to benefit from economies of scale. Imagine, for example, the cost to consumers if 10 competing water companies each had to dig up the local streets to run proprietary water lines to every house in town. The same logic holds true for gas pipes and power grids.

In other cases, such as with the government policies that govern copyrights and patents, governments are seeking to encourage innovation. If inventors had no protection for their inventions, all of their time, effort and money spent writing books, recording songs, and conducting the research and development to create new drugs to combat disease would be wasted when another company who steals the idea is able to create a competing product at a lower cost.

The Downside of Monopolies

While monopolies are great for companies that enjoy the benefits of an exclusive market with no competition, they are often not so great for the consumers that buy their products. Consumers purchasing from a monopoly often find they are paying unjustifiably high prices for inferior-quality goods.

Also, the customer service associated with monopolies is often poor. For example, if the water company in your area provides poor service, it’s not like you have the option of using another provider to help you take a shower and wash your dishes. For these reasons, governments often prefer that consumers have a variety of vendors to choose from when practical.

The U.S. government brought charges against telephone company, AT&T, under the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1974, citing it as a monopoly. The company was broken up into smaller, regional companies in 1984.2

However, monopolies can be equally problematic for would-be business owners as well, because the inability to compete with a monopoly can make it impossible to start a new business. It’s an age-old challenge that remains relevant today, as can be seen by the legal decision to block a merger of Sysco Corp (SYY) and U.S. Foods Inc.

The block was based on the grounds that bringing the two largest food distributors in the country together would create an entity so large and powerful it would stifle competition. The proposed merger between Kraft Foods (KRFT) and H.G. Heinz (HNZ) raised similar concerns, although the merger was eventually permitted to take place.

Monopolies FAQs

What Is the Difference Between Monopolies and Oligopolies?

A monopoly is when one company and its product dominate an entire industry whereby there is little to no competition and consumers must purchase that specific good or service from the one company. An oligopoly is when a small number of firms, as opposed to just one, dominate an entire industry. No one firm dominates the market or has more influence than the others. An oligopoly allows for these firms to collude by restricting supply or fixing prices in order to achieve profits that are above normal market returns.

How Did U.S. Monopolies Affect the Economy in the Late 1800s?

In the 1800s, many monopolies existed in the U.S. that cornered most of the industry. These included John D. Rockefeller and his monopoly on oil, Andrew Carnegie and steel, and Cornelius Vanderbilt and steamboats. These men, to name but a few, dominated their sectors, crushed small businesses, and consolidated power. However, they made these industries more efficient, which resulted in growing the industrial strength of the United States, helping propel it to the global power it would become in the 1900s.

Why Were Few Court Cases Won Against Monopolies During the Gilded Age?

At the time, monopolies, or trusts as they were known, were supported by the government. It wasn’t until the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed in 1890 that the government sought to prevent monopolies. Even when the Act was passed, there were very few cases brought up in violation against it, and most of them were not successful, because of very small windows of judicial interpretation of what constituted a violation.

What Is the Difference Between Monopoly Versus Perfect Competition?

Under a monopoly there is only one firm that offers a product or service, experiences no competition, and sets the price, thus making it a price maker rather than a price taker. Barriers to entry are high in a monopolistic market. In a perfect competition market, there are many sellers and buyers of an identical product or service, firms compete against each other and are, therefore, price takers, not makers, and barriers to entry are low.

Companies in a monopolistic market can earn very high profits in the short run, profits that are higher than normal market returns. In a perfect competition situation, companies cannot earn high profits in the short run, as they are price takers, not makers.

The Bottom Line

While monopolies created by government or government policies are often designed to protect consumers and innovative companies, monopolies created by private enterprises are designed to eliminate the competition and maximize profits.

If one company completely controls a product or service, that company can charge any price it wants. Consumers who will not or cannot pay the price don’t get the product. For reasons both good and bad, the desire and conditions that create monopolies will continue to exist.

Accordingly, the battle to properly regulate them to give consumers some degree of choice and competing businesses the ability to function will also be part of the landscape for decades to come.

How Media Monopolies Are Undermining Democracy and Threatening Net Neutrality

Although headlines about Russia and James Comey have dominated mainstream media for most of Trump’s presidency thus far, damage to democracy has been going on behind the scenes. Advocates of net neutrality are watching in horror as Ajit Pai, head of the Federal Communications Commission, works to destroy net neutrality and other consumer protection regulations.

“Most Americans are not able to get the information that they need to keep themselves safe.” So says Mark Lloyd, the associate general counsel and chief diversity officer at the Federal Communications Commission in 2009-2012. Lloyd, also an author, a professor of communications at USC’s Annenberg School and an Emmy Award-winning journalist, discusses with Robert Scheer media consolidation and consumer protection during this week episode of KCRW’s “Scheer Intelligence.”

Lloyd has written for Truthdig about media consolidation and the communications crisis happening in America, and he expands on these ideas in his discussion with Scheer.

This communications crisis started “before Trump,” Lloyd says. He explains how a lack of effective telecommunications affects health, finances and other crucial factors of Americans’ lives.

“In the U.S., our priorities are to make sure that people are making money in communications,” Lloyd continues, “and not making sure that people are safe with the communications services that they use.”

“So we’re not even talking about whether they’re being informed about trade with China or the war in Syria,” Scheer notes. “We’re talking about, actually, what they need for their well-being.”

The two go on to discuss the FCC, where Lloyd once worked as a lawyer. Lloyd explained that, while at the FCC, he tried to make communications services more accessible to all—but then the 2016 election happened.

He goes on to break down the current battle over net neutrality:

The challenge is that organizations like Google, like Netflix, like Facebook—they don’t really provide you with internet service. What they provide you with is the entertainment, with the application that you need to search the internet, with your ability to connect with your friends and things like that because you’re connected to an application. Internet service providers—Comcast, AT&T, Verizon—those folks actually provide you with internet service. That’s where the rubber meets the road. So Google, Facebook, these other companies, they don’t want to have to pay any more than they have to to have access to you.

Lloyd also explains the constitutional origins of U.S. communications and delves into media consolidation in the U.S.

“There’s nothing radically new here,” Lloyd says of the Trump administration’s stance on net neutrality and consumer protections. “The big challenge is that we have an FCC that is not really even looking at the impact of media consolidation, on what it means to local communities.”